"[Al Simmons] had that swagger of confidence, of defiance. . . . I’ve always classed him next to Ty Cobb as the greatest player I ever saw." — Cy Perkins, Philadelphia Athletics

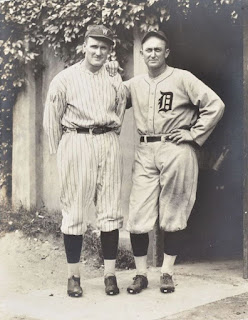

Aloysius Simmons – born Alois Szymanski – posted eye-popping statistics during his tenure in Philadelphia. Between 1925 and 1932, he hit .366 while averaging 25 home runs and 132 RBI per season. Said the venerable Connie Mack of his star outfielder: “I wish I had nine players named Al Simmons.” Beginning in 1933, "Bucketfoot Al" bounced around the American League – Chicago, Detroit, Washington – before joining the senior circuit's Boston Bees (Braves) in 1939. Though no longer a superstar, the 37-year-old was still a formidable batsman, having hit .302 with 21 homers and 95 RBI as a member of the 1938 Senators.

In March 1939, Simmons reported to Boston's spring training camp in Bradenton, Florida. "There is a lot of speculation, Al, on how you will hit," relayed one of the many sportswriters on hand. "The Boston park is fairly spacious, and they say the wind is blowing right in the hitter's faces." Unconcerned by the scribe's theoretical postulation, Simmons retorted: "Maybe so, but it can't be any harder to hit in than Washington's park. Shucks, that's the worst park I ever saw for a long hitter." After answering a few more questions, Simmons excused himself to prepare for batting practice.

In March 1939, Simmons reported to Boston's spring training camp in Bradenton, Florida. "There is a lot of speculation, Al, on how you will hit," relayed one of the many sportswriters on hand. "The Boston park is fairly spacious, and they say the wind is blowing right in the hitter's faces." Unconcerned by the scribe's theoretical postulation, Simmons retorted: "Maybe so, but it can't be any harder to hit in than Washington's park. Shucks, that's the worst park I ever saw for a long hitter." After answering a few more questions, Simmons excused himself to prepare for batting practice.

With a youthful gleam in his eye, baseball's graying warrior stepped up to the plate as his fellow Bees buzzed with anticipation. "Tell him to throw me a curve," Simmons instructed the catcher. The pitcher obliged, and the venerable slugger didn't disappoint: he hit a majestic flyball that cleared the left-field fence with ease. "Now a fastball," yelled Simmons, who promptly hit another impressive blast. "I'll be a monkey's uncle," bellowed Casey Stengel, who was entering his second season as Boston's skipper. "How can the American League let a hitter like that fellow get away?" After smacking another pair of homers, Simmons stepped out of the box to have a drink of water.

During the lull following his initial power display, Simmons was asked about Boston's chances in 1939. "This club can win the National League pennant," replied an optimistic Simmons. Annoyed by the comment, a Cincinnati-based reporter vociferously boasted that the Reds would blow Boston – and all other teams – out of the water in the battle for National League supremacy. "That's what you think!" Simmons barked. "The Reds look good, all right, but they're a young club. Those kids may blow up. They are just like the Athletics were back in 1925. Everybody said we were going to win the American League pennant, and we got tight and were lucky to finish in the league. We're going to have something to say, we Bees."

Unfortunately, the 1939 season turned out to be a bust, as Boston finished the year 25 games under .500. Ironically, Simmons – who hit .282 with 29 extra-base hits during his 93 game stint with the Bees – was acquired by Cincinnati that August. Just as the native newshound had predicted in the spring, the Reds would go on to capture the National League pennant, though Simmons had little to do with their success. Relegated to a pinch-hitting role, the aging slugger posted an anemic .143 average (3-for-21) down the stretch. Simmons, who had previously hit .333 with six home runs in three World Series appearances with Philadelphia, went 1-for-4 during the 1939 Fall Classic – a laughable four-game affair versus the Yankees. — BK2

"It was something to see. When Al Simmons would grab hold of a ball bat and dig in, he’d squeeze the handle of that doggone thing and throw the barrel of that bat toward the pitcher in his warm-up swings . . . he would look so bloomin’ mad, even in batting practice." — Tommy Henrich